Exhibition

Friedrich Kiesler: Architect, Artist, Visionary

Rediscovered Modern I

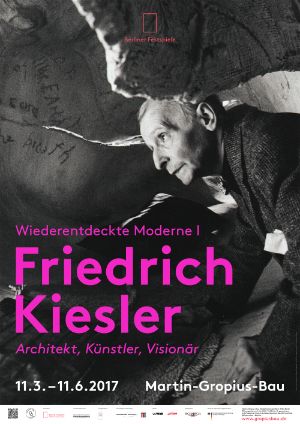

Exhibition poster “Rediscovered Modern I. Friedrich Kiesler: Architect, Artist, Visionary”. Image: Friedrich Kiesler during his work on the sculpture “Bucephalus”, around 1964 Photo: Adelaide de Menil © Friedrich Kiesler Foundation. Poster design Scholz & Volkmer

Friedrich Kiesler, born 1890 in Czernowitz (Chernivtsi), died 1965 in New York, was an Austro-American architect, stage designer, designer, artist and theoretician. His artistic approach blurring boundaries between individual artistic genres, his concept of an endlessly flowing space and his holistic theory of design Correalism belong to the greatest visions of the 20th century and enjoy undiminished topicality. Over and above this, Kiesler was a central figure in the network of New York’s aesthetic community, and his circle of friends reads like a Who-is-Who of the avant-garde.

Martin-Gropius-Bau devoted an exhibition to the universal artist Friedrich Kiesler, in which his complex oeuvre is presented in all its facets for the first time in Germany. Central projects, important artistic friendships and collective works illustrated his importance in 20th-century architecture and art history, and mapped out his environment.

Berlin is almost predestined for this: It is the city in which Kiesler celebrated his first great success with an electro-mechanic stage design for Karel Čapeks W.U.R. (R.U.R.) Werstands Universal Robots in 1923 at the Theater am Kurfürstendamm and literally jumped feet first into the avant-garde scene. A year later in Vienna he caused a furor with the exhibition design of the “Internationale Ausstellung neuer Theatertechnik”, which he also curated, and another sensation with his Space Stage (Raumbühne) as the central exhibition piece. In 1925, Josef Hoffmann invited him to design the Austrian theatrical section for the “Exposition Internationale des Arts Décoratifs et Industriels Modernes” in Paris. He used this commission to present his City in Space, his vision of a futuristic floating city, as an exemplary exhibition structure. In 1926 he travelled to New York, to once again organize an “International Theatre Exposition”.

Kiesler left Europe with avant-garde projects in his luggage. Arriving with great expectations, many remain largely unfulfilled initially. His ideas seemed too avant-garde for the new world. Kiesler quickly came to terms with the harsh reality of 1920s New York and found a successful occupation designing display windows and business premises. With the Film Guild Cinema, Kiesler designed the first 100% Cinema in 1929 in New York, an icon of modern cinema architecture, indeed, with additional projections on side walls and the ceiling of the auditorium it is an early example of Virtual Reality.

Into the 1930s Kiesler worked on furniture and lamp designs and erected his Space House, his vision of a family home as a 1:1 model in the show rooms of the Modernage Furniture Company in New York in 1933. Many core issues of Kiesler’s theory on design, respectively architecture, above all his “space-time architecture” concept are formulated here for the first time.

After an interruption of more than ten years, Kiesler began to work in theatre again in 1934. He made a successful début in the New York theatre scene with the stage design for George Antheil’s Opera Helen Retires, which led to an engagement at the Juilliard School of Music. Around 60 decors were created there during his teaching career of 25 years. With the Woodstock Theatre (1929) and the Universal Theatre (1959-62) Kiesler created two prototypes of multi-functional cultural venues, which were however only realised as models.

From 1937 to 1941, Kiesler directed the Laboratory for Design Correlation at Columbia University in New York and developed his theory of Correalism, an holistic approach to design based on scientific analysis that revolved around the human being. Kiesler’s research led him to concentrate intensively on human perception and he developed the Vision Machine, through which he sought to visualize human vision as an active process. These studies formed the basis of his later exhibition designs. In the course of the 1940s Kiesler also worked on two extensive book projects – a publication of his theory of design of Correalism, and a cultural anthropology of architecture with the sonorous title “Magic Architecture”. Both writings remained unpublished.

At the same time, Kiesler also designed several spectacular exhibition rooms: Peggy Guggenheim’s “Art of This Century Gallery”, the “Russian American Exhibition”, a “Hall of Ecology” in the American Natural History Museum, the exhibition “Bloodflames 1947”, as well as the “Exposition Internationale du Surréalisme”. All of these were redolent of his close relationship to surrealists in exile in New York. Kiesler was an artist’s artist. Exchange and collaboration with artistic colleagues were of immense importance to him. This is especially true of Marcel Duchamp. Kiesler published his first article about Duchamp‘s The Large Glass in an American magazine (Architectural Record, 1937). Duchamp lived in the Kiesler’s apartment for almost a year; they played chess together, shared their interest in natural science, technical innovations and the operating principles of human perception. They worked on exhibitions and design magazines together. However, their ways parted after a fight in New York’s surrealist community.

Kiesler created an extensive environmental sculpture from parts of the surrealistic set design for the opera The Poor Sailor (Le Pauvre Matelot) by Darius Milhaud, the so-called Rockefeller Galaxy, which was shown in the 1952 exhibition “15 Americans” at MoMA. Based on this sculpture, Kiesler developed a further Galaxy sculpture for Philip Johnson’s Glass House in New Canaan. Further so-called Galaxy paintings were created: Clusters of picture plates were arranged at meticulously defined intervals to each other, partly on the floors, walls and ceilings. The “space in between”, the individual picture plates, was considered as important as the paintings themselves.

Kiesler always maintained that every person has a “basic design idea” – the work with “space” could be designated as such for him. Space, especially endlessly flowing space, is a key concept throughout all of Kiesler’s work. In 1950 he created an egg-formed Endless House model for the first time. During the 1950s he refined this concept and received a grant in 1958 to erect a 1:1 model of an Endless House in MoMA’s Sculpture Garden. Even if it failed to be completed, it was still undisputedly one of the icons of visionary 20th-century architecture.

The only one of Kiesler’s buildings to actually be built was opened in Jerusalem in 1965: the Shrine of the Book, planned by Kiesler together with Armand Bartos. The symbolically highly charged building containing Old Testament scrolls found near the Dead Sea, as well as the unbuilt Grotto for Meditation in New Harmony, Indiana, were indicative of the great interest in sacred spaces in Kiesler’s late work.

During the years 1964-1965, Kiesler worked on large environments composed of individual sculptures cast in aluminium or bronze. Both his sculpture Bucephalus, a reference to Alexander the Great’s battle steed, as well as the large environment Us, You, Me, united Kiesler’s complete oeuvre. In a way, the walk-through sculpture Bucephalus, a small mythologically and symbolically charged Endless House equipped with theatrical sound effects, represented the sum of all his earlier projects. Nowadays Kiesler’s sculptural projects are barely known and can be discovered for the first time in Berlin as an essential component of his wide-ranging oeuvre in the exhibition at Martin-Gropius-Bau.