Louise Bourgeois, Spider, 1997 © The Easton Foundation/VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2022, photo: Erika Ede

Exhibition texts

Louise Bourgeois: The Woven Child

Read all exhibition texts during or after your visit to the show and learn more about the first major retrospective of Louise Bourgeois, which focuses exclusively on the works that she made with fabrics and textiles during the final chapter of her storied career.

Introduction

In the final two decades of her life, Louise Bourgeois (1911–2010) embarked on a daring new chapter in the development of her art. During this period she created an astonishingly inventive group of sculptures, drawings and installations that incorporated domestic fabrics, including clothing, linens and tapestry fragments, often sourced from her own household and personal history. Many of these late works returned to, and recalibrated, the core concerns and formal devices of her earlier art, exploring sexual ambiguities and harrowing psychological and social relationships.

Bourgeois’s use of soft materials – including the “second skin” of her own clothes – often imbues these works with a sensuous quality and an almost tactile sense of vulnerability and intimacy. She saw the actions involved in fabricating them in metaphorical terms, relating the cutting, ripping, sewing and joining to notions of reparation and to the bodily expression of psychic tensions.

As the daughter of tapestry restorers, the artist’s turn to textiles in her eighties could be seen as a renewed exploration of her past. At the same time, her fabric works invite us to reimagine the meanings of mending, including a concept of emotional repair that – rather than neatly sewing everything up – can expand and refresh our perspectives.

The exhibition is organised by the Hayward Gallery, London, in association with Gropius Bau, Berlin

Curators: Ralph Rugoff, Director, Hayward Gallery, and Julienne Lorz, former Chief Curator, Gropius Bau

This exhibition has been funded by the German Federal Cultural Foundation

Gropius Bau is supported by the the Federal Government Commissioner for Culture and the Media and by Neustart Kultur

Cell VII, 1998

From 1991 onwards, Bourgeois produced a series of room-like environments, titled “Cells”. In these installations personal artifacts and various sculptural elements are arranged in self-contained and highly charged compositions that often relate to the artist’s personal history, as well as to memory, architecture and the five senses.

The dream-like installation Cell VII features a bronze scale model of the artist’s childhood home in Choisy-le-Roi, France. Loosely hanging from metal armatures and cattle bones, clothing that had belonged to Bourgeois’s mother and garments from her youth become vestiges of memory which haunt the space.

Louise Bourgeois, Cell VII, 1998

© The Easton Foundation/VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2022 and VAGA at ARS, NY, Photo: Peter Bellamy

Untitled, 1996

Louise Bourgeois, Untitled, 1996

© The Easton Foundation/VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2022 and VAGA at ARS, NY, Photo: Rom Amstutz

Bourgeois saved clothing throughout her life, including dresses and undergarments from her childhood and items that had belonged to her mother. In the mid-1990s, she began incorporating this material into artworks. In a series of “pole pieces”, she displayed garments that were especially evocative of her past – ones she would not have cut or reconfigured. For Bourgeois, these clothes were as significant as the pages of her diary in their ability to hold the memory of people, places and events as well as the touch of her own body.

Suspended from cattle bones, the delicate slips and nightclothes in this work appear to float like ghosts. The black sequined dress and the beige silk blouse are loosely stuffed, giving them sculptural volume, whilst the bone hanger protrudes from the neck of the latter like a gruesome head. Welded into the base of the sculpture are the words “Seamstress, Mistress, Distress, Stress”; a play on words that references Bourgeois’s family history and its psychological impact on her.

Needle (Fuseau), 1992

“When I was growing up, all the women in my house were using needles. I’ve always had a fascination with the needle, the magic power of the needle. The needle is used to repair the damage. It’s a claim to forgiveness. It is never aggressive, it’s not a pin.” – Louise Bourgeois

Louise Bourgeois, Needle (Fuseau), 1992

© The Easton Foundation/VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2022 and VAGA at ARS, NY, Photo: JJYPHOTO

Couple IV, 1997

Louise Bourgeois, Couple IV [Paar IV] , 1997

© The Easton Foundation/VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2022 and VAGA at ARS, NY, Photo: Christopher Burke

One from a series of fabric couple sculptures made in the late 1990s, this pair of headless, copulating figures is encased in an antique vitrine, like a carefully preserved specimen. The work’s claustrophobic, almost coffin-like sense of containment suggests the suffocating character of relationships driven by a fear of separation or abandonment. For Bourgeois, the female figure’s wooden leg symbolises psychic injury or a loss of equilibrium. Bourgeois was fascinated by prosthetic limbs, which she first encountered during her childhood in France in the aftermath of the First World War, and in her late sculptures she increasingly included references to prostheses, crutches and amputees. Bourgeois saw the prosthesis as something which, like art, allows one to survive intense emotional suffering. Bourgeois noted that this sculpture alluded to the “primal scene”, a psychoanalytic concept describing a child’s real or imagined vision of a sexual encounter between its parents, which is perceived as an act of violence. This blending of sexuality and death, pain and pleasure, passive and active, gives the work an additional disturbing dynamic.

Eugénie Grandet, 2009

Bourgeois was fascinated by the character of Eugénie Grandet, a young woman with an oppressive father who is the subject of Honoré de Balzac’s eponymous 1833 novel. Bourgeois explained: “I have a great longing for revenge against my father, who tried to make me into an Eugénie Grandet.”

In 2009, near the end of her life, Bourgeois created these 16 panels using handkerchiefs and tea towels from the trousseau of linens she brought from France when she moved to the United States 70 years earlier. Collaged with artificial flowers, pearls, buttons and other elements taken from Bourgeois’s own hats and clothing, as well as from the sewing box she had assembled over the years, they evoke unrealised desires and the passing of time.

Louise Bourgeois, Eugénie Grandet, 2009

© The Easton Foundation/VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2022 and VAGA at ARS, NY, Photo: Christopher Burke

Cell XXV (The view of the world of the jealous wife), 2001

Louise Bourgeois, Cell XXV (The view of the world of the jealous wife), 2001

© The Easton Foundation/VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2022 und VAGA at ARS, NY, photo: Christopher Burke

Within this circular enclosure, its contents visible from all sides, Bourgeois arranged three of her own garments on dressmaker’s mannequins: a striking blue cocktail dress; a patterned white day dress; and a short blouse encircled by a floating ring of blue, bell-shaped pieces of glass. Two large, white marble spheres are positioned on the floor. In another context they might conjure breasts but here, visually aligning with the light-coloured dress, they create a phallic composition at the centre of the Cell. This work reflects Bourgeois’s interest in the distorting effect of jealousy on one’s relationship to others.

Lady in Waiting, 2003

Constructed from reclaimed wooden doors and windows, a claustrophobic room encloses a solitary spider woman, with steel legs and a body made of tapestry, seated on an armchair. Five threads extend from her mouth to connect with the spools resting on the windowsill above her. The threads symbolise the flow of time and allude to the five members of Bourgeois’s family – both the one in which she was raised and the one she had with her husband, art historian Robert Goldwater.

The spider constructs its web out of its own body, which Bourgeois saw as a metaphor for her creative process. She also identified with her mother’s work as a tapestry restorer. Yet Lady in Waiting can also be seen as an emblem of a life not lived. Blending into the back of the chair which is upholstered with a tapestry fabric similar to its body, the spider woman waits in a state of diminished visibility, hiding as if to protect itself.

Louise Bourgeois, Lady in waiting, 2003

© The Easton Foundation/VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2022 und VAGA at ARS, NY, photo: Christopher Burke

Untitled, 2002

Louise Bourgeois, Untitled, 2002

© The Easton Foundation/VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2022 and VAGA at ARS, NY, Photo: Christopher Burke

In 1998 Bourgeois began making a series of stuffed fabric heads, using various textiles including cloth, towels, cotton ticking, patterned garments, needlepoint and tapestry.

Rather than making conventional likenesses of individual people, Bourgeois was interested in portraying a range of emotional and psychological states. Some of these heads feature more than one face, evoking the coexistence of contradictory or ambivalent feelings and attitudes.

High Heels, 1998

Made from fragments of grey and black clothing, High Heels presents a kneeling, armless figure lying face down and twisted to expose its bulbous buttocks and breasts. The figure’s legs culminate in a pair of welded steel shoes with pointed heels.

The figure’s posture is reminiscent of a 1994 etching by Bourgeois in which a cat, its hind paws in high heeled shoes, is depicted in a similar position, as if in heat. In High Heels, Bourgeois has accentuated the contrast between the submissive figure stitched from soft fabrics and the implied danger and aggression of the spiked metal shoes. The psychosexual dynamics of sadism and masochism are united in this work to create an uneasy and ambivalent portrayal of desire and sexuality.

Louise Bourgeois, High heels, 1998

© The Easton Foundation/VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2022 und VAGA at ARS, NY, photo: Christopher Burke

Pierre, 1998

Louise Bourgeois, Pierre, 1998

© The Easton Foundation/VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2022 und VAGA at ARS, NY, photo: Christopher Burke

Pierre was the first of Bourgeois’s series of fabric heads, and is titled after the artist’s late brother, who was institutionalised in 1945 and remained in an asylum for the rest of his life. Bourgeois felt increasingly isolated from him and guilty for her absence. A telling feature of this head is its missing ear, which symbolises their lack of communication.

Composed of several pieces of the same pink fabric, as if to suggest a fragmented self, Pierre is held together by notably loose stitching. This style of sewing conveys a palpable sense of psychic tension and is employed in many of Bourgeois’s early fabric figures. It could be read as the physical representation of psychological repair, much as scars are the residue of healing.

Arch of Hysteria, 2004

This selection of small fabric sculptures, which Bourgeois began in the early 2000s, evokes a range of conflicted mental states. Many possess fantastical appearances and some suggest a mordant wit at play, such as the figure with a pair of egg tongs attached to its head. The hanging Arch of Hysteria, constructed from boldly striped fabric, depicts a male body in a state of extreme physical tension as a metaphor for underlying psychic distress.

Louise Bourgeois, Arch of Hysteria, 2004

© The Easton Foundation/VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2022 und VAGA at ARS, NY, photo: Christopher Burke

Spit or Star, 1986

Louise Bourgeois, Spit or Star, 1986

© The Easton Foundation/VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2022 and VAGA at ARS, NY, Photo: Peter Bellamy

This group of works on paper presents some of the key motifs and processes in Bourgeois’s fabric work: cutting, mending, sewing and the needle. Spit or Star and Mending (1989) are the earliest works in the exhibition and seemingly anticipated the artist’s turn to working with fabric in the 1990s. Spit or Star depicts two pairs of scissors floating above a landscape. Bourgeois made several drawings of cutting implements around this time. Her interest in scissors and shears relates to their ambiguity as both instruments of creativity and violence; to the topiary boxwood trees of her youth, pruned to grow stronger; and to the cutting of the umbilical cord, which symbolises the interdependent relationship of mother and child.

Untitled 1998

“It is not an image I am seeking. It is not an idea. It is an emotion you want to recreate, an emotion of wanting, of giving, and of destroying.” – Louise Bourgeois

Louise Bourgeois, Untitled, 1996

© The Easton Foundation/VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2022 und VAGA at ARS, NY, photo: Allen Finkelman

Cell XXI (Portrait), 2000

Louise Bourgeois, Cell XXI, 2000

© The Easton Foundation/VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2022 und VAGA at ARS, NY, photo: Christopher Burke

Bourgeois created her “portrait cells” with the intention of representing particular psychological states. Smaller in scale and focussed on a specific dynamic or situation, they are a distinct subgroup of her larger and more complex Cell installations.

This is one of Bourgeois’s most ambiguous portrait cells. Made from old towels and dressing gowns, this enigmatic work fuses figurative and abstract, male and female, within a single sculptural form. One side resembles a torso with breast-like appendages, while the other features a protruding pink tongue. This duality imbues the work with an unsettling indeterminacy and precariousness.

Cell XXIV (Portrait), 2001

Louise Bourgeois, Cell XXIV (Portrait), 2001

© The Easton Foundation/VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2022 und VAGA at ARS, NY, photo: Christopher Burke

In Cell XXIV (Portrait), three conjoined heads, each with two faces, hang together as a single sculptural form. The composition is roughly stitched together from pieces of black fabric, a colour that Bourgeois associated with depression, mourning and melancholia. Mirrors positioned in the corners of the Cell further multiply the six faces, providing various perspectives and serving to accentuate a sense of scrutiny, fragmentation and unease.

The Reticent Child, 2003

Louise Bourgeois, The Reticent Child, 2003

© The Easton Foundation/VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2022 and VAGA at ARS, NY, Photo: Christopher Burke

This work was inspired by Bourgeois’s attempts at understanding the origins of reticence and withdrawal in her youngest son, Alain, whom she always referred to as the “reticent child”. The small figurative sculptures in this melancholy diorama were intended to represent his birth and early life. The figures appear contorted and animated by a concave mirror, which adds to the work’s sense of narrative and theatricality, while also highlighting the distorting effects of memory. In a text accompanying the work when it was first exhibited at the Sigmund Freud Museum in Vienna, in 2003, Bourgeois wrote: “There is a child who simply refused to be born. His birth was quite late. Was there something that he perceived that prevented him from wanting to leave the womb and go out into the world? How much of who he will be, his feelings and actions, will be pre-determined by this refusal to appear? How will this child face the future? Will he be shy, reduced to silence, awkward or even hostile? He is the reticent child…”

Spider, 1997

The spider is a recurrent motif in Bourgeois’s work, realised most prominently in a series of large-scale bronze sculptures made in the 1990s and 2000s. The spider here straddles the steel-mesh Cell enclosure below, as if protecting its web. A tapestry-covered chair occupies the centre of the enclosure and fragments of tapestry are affixed to its walls. A selection of personal belongings – hanging bottles of Shalimar perfume (Bourgeois’s favourite), a medallion, a stopped watch – create an atmosphere of recollection and lost time.

Three glass eggs wrapped in fabric are positioned under the spider’s abdomen. Bourgeois associated spiders with her mother, a weaver and restorer of antique tapestries, and with her own identity as an artist. This towering sculpture also evokes the spider’s character as a predator that entraps its prey and cannibalises its mates, suggesting Bourgeois’s more complex and ambivalent conception of motherhood and sexuality. “I came from a family of repairers. The spider is a repairer. If you bash into the web of a spider, she doesn’t get mad. She weaves and repairs it.“ – Louise Bourgeois

Louise Bourgeois, Spider, 1997

© The Easton Foundation/VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2022, photo: Erika Ede

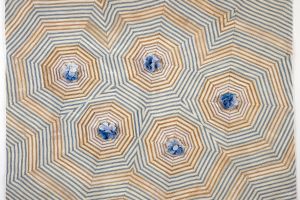

Untitled, 2006

Louise Bourgeois, Untitled,2006

© The Easton Foundation/VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2022 und VAGA at ARS, NY, photo: Christopher Burke

In this series of fabric collages, Bourgeois cut up, repositioned and sewed together pieces of striped and patterned clothing and domestic fabrics in intersecting, sometimes concentric circles. These kaleidoscopic compositions resemble spiders’ webs, an image that represented “a friendly refuge” for Bourgeois and was a visual metaphor for her own creative process. The five nodes seen in many of the works – some with flowers at their centres – represent both the family Bourgeois grew up with, and the one she had with her husband. Though the fabric collages retain a strong visual formalism, their construction from domestic materials, and thus their associations with memory and the body, betrays deep emotional resonance.

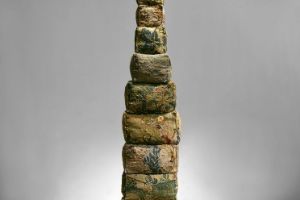

Untitled, 2000

In 2000, Bourgeois began making a series of sculptural “progressions” which revisited the vertical forms of her segmented Personage sculptures from the 1950s. Made from clothing, bed linen, terry cloth, tapestry and upholstery, the individual sculptures vary in composition, with their separate blocks increasing or decreasing in size as they ascend.

For Bourgeois, the predictability of formal repetition served to reassert a sense of order to chaotic feelings, despite the potential of each element to pivot and rotate. She explained: “With geometry, you have a consistent set of rules. There is certitude, which is the exact opposite of the emotional world I inhabit.” The soft materials which form the stacked fabric towers provide a sense of vulnerability and intimacy, while also remaining flexible, adaptable and resilient.

Louise Bourgeois, Untitled, 2000

© The Easton Foundation/VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2022 and VAGA at ARS, NY, Photo: Christopher Burke

Spiral Woman, 2003

Louise Bourgeois, Spiral Woman [Spiral-Frau], 2003

© The Easton Foundation/VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2022 and VAGA at ARS, NY, Photo: Christopher Burke

Composed entirely of black cloth, this life-sized figure is consumed by its spiral form, which begins at the torso and encompasses its entire upper body and head. In Bourgeois’s iconography, the twisted body evokes nausea, dizziness and disorientation – physical manifestations of psychological states such as fear, anxiety, homesickness and alienation. Like a similar bronze sculpture that Bourgeois made in 1984, this fabric Spiral Woman hangs from a single point. The rotational movement implied by the spiral is emphasised by the sculpture’s potential to twist and turn in real space.

Bourgeois was interested in the spiral because it has two directions; as she said: “Beginning at the outside is the fear of losing control; the winding in is a tightening, a retreating, a compacting to the point of disappearance [...] The move outward is a representation of giving, and giving up control; of trust, positive energy, of life itself.”

Untitled, 2005

During the last five years of her life, Bourgeois created this series of four large wooden vitrines, each displaying various sculptural motifs – the stacked progression, the armature with its rubber teardrop form and spools of thread, and the bulbous hanging sacks or stuffed mounds. Though more or less abstract, these forms also conjure our physical nature. “To me, a sculpture is the body”, Bourgeois said. “My body is my sculpture.” In Untitled a sagging cluster of cheesecloth pouches hangs around a central pole, bringing to mind the flaccidity of skin and the body. These empty sacks are particularly evocative of wombs and breasts, and reference aging and loss.

Louise Bourgeois, Untitled, 2005

© The Easton Foundation/VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2022 and VAGA at ARS, NY, Photo: Christopher Burke

Untitled, 2010

Louise Bourgeois, Untitled, 2010

© The Easton Foundation/VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2022 and VAGA at ARS, NY, Photo: Christopher Burke

Created in the months before her death, Untitled (2010) incorporates a collection of the artist’s own berets, stuffed and arranged atop a large armless torso lying on a steel platform. The berets recall both breasts and a hilly landscape, and yet they also seem abstract and enigmatic in form. The sharp contrast of the soft fabric against the steel surface on which they rest reflects Bourgeois’s interest in reconciling apparent opposites: hard and soft, geometric and organic, trauma and reparation, figuration and abstraction.