The Singing Project writing desk, 2022

© Ayumi Paul

Bless the Moon

Natasha Ginwala in conversation with Ayumi Paul

Forgive us, we blamed you

for floods, for the flush of blood,

for men who are also wolves, even

though you could pull the tide in

by her hair, we tell everyone

we walked all over you.

— Warsan Shire, Bless The Moon

Natasha Ginwala: In this poem, there feels to me a call for environmental justice at first in the form of “mutual recognition” – just as much as it is a serenade to the moon, a blessing. And it brings me to the way in which you approach the lunar cycle in The Singing Project as time-keeping that is cosmic yet also collective, addressing each person who walks into the room.

Ayumi Paul: To me it is an act of common sense to listen to how the moon breathes and how the earth breathes, how time breathes and how stones breathe. What makes our bodies has existed much longer than the human species and those elements are naturally attuned to rhythms such as the lunar cycle. These rhythms also anchor the planning of The Singing Project – an ongoing series of singing workshops I started at the Gropius Bau in the summer of 2021 – entailing an invitation to something that has been here before us and will continue to be after we have passed away. Maybe similar to the poem by Warsan Shire, it is a way of bowing to life, instead of walking all over it; a way of honouring that I do not breathe alone but breathe and am being breathed, and a reminder that everybody is part of this cycle.

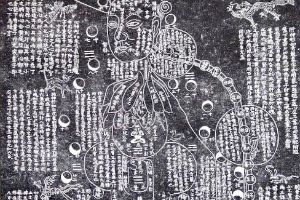

The collective practice of The Singing Project is also rooted in listening – “to be all ear” (a translation of the German idiom: “ganz Ohr sein”) – which is something I propose very regularly in the workshops. There is a Buddhist deity called Guanyin whose name literally translates into: “The one who hears the sounds of the world” who is a strong inspiration for me, too.

Natasha Ginwala: I really enjoy the idea of “The one who hears the sounds of the world” as not only a sacred entity but also aligning with the role of an artist such as yourself. I’m also interested in thinking about instruments that measure terrestrial levels and seismic activity such as the geophone and seismograph in this way, as sounding “liquid earth”, which is also an aspect present in your work through listening and scoring. Could you speak to these elements in your practice?

Groove cutting, 2020, photography © Ayumi Paul

Ayumi Paul: I use instruments that pick up the vibrational structure underground as well as hydrophones to be able to listen to acoustic signals underwater, and mostly as a tool for learning. This visualisation, for instance, is an excerpt of me playing a composition by Johann Sebastian Bach on my violin. A device measured the sounding vibration of the air while playing, transferred the movement to a needle that then simultaneously scratched these curvy traces onto a plate: 678 metres of music in total. This example draws attention to the fact that every device-based recording is actually a translational process. Geophones and seismographs for lower frequencies do not record per se, they convert seismic movement into voltage; their acoustic and visual recordings are translations of the original vibration.

The inherent pulsing inside the earth body is in constant interplay with our bodies and our surroundings. All life sounds through our bodies as they are natural pick-ups, direct-to-body recordings. If I place my elbows or seating bones on the ground, I sense vibration; if I were to place my hand on yours, I should be able to hear your music. It is only a question of practice to be able to hear those sounds and practice takes time.

However, what I also observe is an enormous imbalance between the use of technical devices and the use of our senses. Floods of data and information are available and reveal the intricacy and violence of economic and socio-political belief systems. I wonder if we are actually able to hear that, or if we are only re–acting.

With this in mind, I aim to compose seeds or keys of reconnections to our senses and to our intuitive ability to read signs rather than relying on alphabets solely. Ultimately, I am interested in practising my body to hear more than a device is able to detect. The act of listening for me eventually is a co-creation: I look at the flower – the flower looks at me, for example, is the title of a recent sound piece of mine that speaks to this permeable process.

Natasha Ginwala: This title reveals a mutuality. It reminds me of the way the philosopher Catherine Malabou in her essay Rethinking Mutual Aid (2020) thinks about mutual aid in society as an acknowledgement of the “contingent dynamic relation” between living beings since altruism and interdependency stem from the world and mind as constitutive organs. Could you share more about how you commence your workshops?

Ayumi Paul: I begin the workshops with storytelling, breathwork and meditations, also often with laughing. I envision it as the imaginary changing room for everybody participating in the workshop, including myself, to put their bags of attachments into a locker – explorers travel lightly.

Natasha Ginwala: Is there a particular element of breathwork or meditation that you would like to draw our attention to? And how do you spend time learning from the range of somatic and spiritual practices that find resonance in your workshops?

Ayumi Paul: The foundational element of breathwork is very simple: It’s to breathe in (through the nose) and recognise that you’re breathing in, and to breathe out and notice this movement as well.

In retrospect, it seems as if I began preparing myself for these workshops at the age of five when I started to play the violin. In a calculation I made a few years ago, I’ve noticed that I had approximately practised the violin for around 45.000 hours until then. There is one particular musical composition that I have played almost every day for the past 25 years. Repeating the same melodies is like walking through the same forest again and again. It is always different and there is always more to discover.

I have also been training in a variety of dance practices such as Butoh and Gaga and have been studying different paths of ancient somatic and philosophical practices since my late teenage years. Science has been influential to the workshops, especially physics, neurobiology and bioacoustics.

Some of my most important teachers have crossed my path in the form of spirits and in the dream world. I believe there are many more ways of learning than linear learning. For the workshops, I want to understand where the many aspects of my learning touch each other and how to integrate that into an embodied vocal practice that is immediately applicable by everyone.

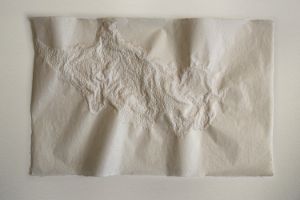

Ayumi Paul, Salt song, 2022, 70 x 42 cm, salt, water, sound on paper © Ayumi Paul

Natasha Ginwala: Could you indicate how the change in seasons and length of daylight play a role in the way you compose workshops and the texture these circadian rhythms bring with them?

Ayumi Paul: In Japanese, the word shiki (四季) is used when speaking of one of the four seasons of spring, summer, fall and winter and then there is the word kisetsu (季節), which also translates into season but in the sense of “the time of the year” (which is similar to the original meaning of the German word for season: “Jahreszeit”). I like the word kisetsu because it calls me into listening closer to the shades of each moment and the multitude of circadian and other intrinsic rhythms it is held by. Practising awareness for such rhythms transmits a sense of genuine belonging, which allows us to sound and be playful within a greater whole.

itoshimeba

ki mo katarikuru

haru no tsuki

if i give my tenderness and love

a tree, too, will speak to me

spring moon

— Heinosuke Gosho

Natasha Ginwala: There has been a range of emotions that have been released into the Gropius Bau as part of The Singing Project, including grief. The labour of “cleaning” plays a crucial role for you, in terms of what it means to inhabit and make a space for others to join in. How do you imagine these traces and practices will transform the site?

Ayumi Paul: I began the project by asking myself: “What if there was a space where people could always sing freely together; what if a museum turned into a place of continuous song and what would need to be done to extend that as far as possible?”

The Singing Project practises singing not through repeating songs by others but through sounding in the present as a self-creating human and beyond-human mother tongue. It forms mesmerising worlds of sounds but can equally be incorporated into daily life as another layer of being in communion with each other, including other forms of life and other timelines. For instance, it can help when in conflict and prior to working on something together, to share grief and take care of the departed and as a way of soothing and caressing each other, of passing on memories and knowledge, of self-pleasure, praise, joy and follyness. The possibilities are endless – why not try to develop new sensibilities to connect to the spectacular complexity within and around us?

Ayumi Paul, Salt song, 2022, 70 x 42 cm, salt, water, sound on paper © Ayumi Paul

Everything influences each other even if we do not immediately see it. These, for example, are crystalised songs, shaped by the interplay of salt, water, air and my voice on paper. Singing as one body without fixed leadership and in constant flux, guided only by being open and permeable, requires courage for change and kindness with one another. And to your questions of how I think these practices will transform the site, I am sure these sounds will naturally create a resonance that inspires more of it and beyond. But since this project emphasises collaboration, reciprocity and research rather than production, the impact or transformation of any site will always depend on the care and active practice by the people.

For Haruko

Hey Baby you betta

Hurry it up!

Because

Since you went totally

Off

I seen a full moon

I seen a half moon

I seen a quarter moon

I seen no moon whatsoever!

(...)

— June Jordan, Poem About Process And Progress

Ayumi Paul studied classical violin at the Hanns Eisler School of Music Berlin and Indiana University Bloomington in the United States. She toured internationally from 2000–2015, playing at concert halls around the world. Increasingly, her works are performed in museums and galleries. Her first institutional solo exhibition took place at the Kunsthalle in Osnabrück in the spring of 2020. In 2021, she was granted a residency at Villa Massimo in Rome. Ayumi Paul is this year’s Artist in Residence at the Gropius Bau.

Natasha Ginwala is Associate Curator at Large at the Gropius Bau. She is the artistic director of COLOMBOSCOPE, Colombo, Sri Lanka and was the artistic director of the 13th Gwangju Biennale with Defne Ayas.

White Cloud Tempel. An image from the White Cloud Taoist temple in China, sent to Ayumi Paul by her friend Lingji Hon