Germany’s Colonial Entanglements in the Pacific

Anja Schwarz

This essay is an excerpt from a lecture given by Anja Schwarz, Professor of Cultural Studies at the University of Potsdam, as part of Daniel Boyd’s exhibition RAINBOW SERPENT (VERSION) at the Gropius Bau. In her lecture, Schwarz focused on colonies of Germany in the Pacific and the role of German-speaking agents within the settler colonies in Australia.

The text addresses colonial violence. Members of First Nations and Great Ocean Indigenous communities are advised that people mentioned in writing or depicted in accompanying artworks may have passed away.

In being invited to reflect on Germany’s colonial entanglements in the Pacific in the context of Daniel Boyd’s exhibition “RAINBOW SERPENT (VERSION)”, I would first like to acknowledge by name the Kudjala, Ghungalu, Wangerriburra, Wakka Wakka, Gubbi Gubbi, Kuku Yalanji, Yuggera and Bundjalung People, of whom Daniel Boyd is a member, and their ongoing relationship with Country. I would also like to acknowledge the Gadigal and Wangal People, on whose Country Daniel Boyd works as an artist.

With this introductory statement, I have tried to translate parts of an “Acknowlegement of Country” that is common in Australian institutions into the German context. There are no recipes or strict guidelines for such an acknowledgement. (1) However, the respective “Country” (in the broadest sense: the land one is referring to) should be named as precisely as possible, and First Nations’ special relationship to Country should be acknowledged. (2) This form of situating is understood as generative for the exchange of knowledge that takes place on or about Country. The speaker of such an acknowledgement is also invited to elaborate on how the occasion of the conversation relates to Country.

In a certain sense, this invitation to relationality also corresponds to the intention of my short contribution. At first, it might seem strange to relate the paintings of an Australian First Nations artist to German colonial history in the Pacific – especially since the so-called German protectorates in the Pacific did not include Australia and the Pacific island of Vanuatu, where part of Daniel Boyd’s family hails from. But instead of talking about German colonies, I would like to trace Germany’s relations, interconnections or entanglements in the wider Pacific region that became apparent to me while viewing the exhibition. These relations go far beyond the period of formal colonialism between 1884 and 1914. Since the second half of the 18th century, German sailors, soldiers, drafters and scientists regularly travelled to the Pacific. From the 19th century onwards, trade representatives of various German states were permanently present in the region; and we should not forget that German missionary societies, among others, had a devastating impact on Oceanic knowledge traditions.

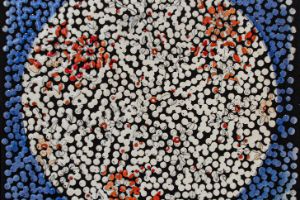

Plate

Daniel Boyd, Untitled (FDWHBFTU), 2022

© Gropius Bau, photo: Luis Kürschner

Daniel Boyd’s version of a plate from the estate of Robert Louis Stevenson, which is held in a museum at the University of Sydney, could be thought of as the inspiration for this undertaking. Stevenson was the author of popular novels like Treasure Island and lived in Apia on Samoa from 1890 onwards, where the plate was part of his household. Not just as a result of Boyd’s specific painting technique, but also of what it depicts, the plate breaks with what we expect from art about and from the Pacific: instead of flowers like the hibiscus or tiaré that we might consider exotic, we see a Victorian everyday object with a decidedly English floral motif. It raises the question of how this piece of England came to Samoa and what impact this particular history has on the present. Translated into the intention of my lecture: What does it mean to trace pieces of German colonial history in the Pacific in relation to some of Boyd’s paintings?

Mai

Daniel Boyd’s painting of Mai, the first Polynesian man to visit Britain, is based on a large-scale portrait by the British painter Joshua Reynolds. Mai travelled from the Society Islands to London in 1774 with Captain James Cook on his second circumnavigation of the globe. Prior to this, he had witnessed the often violent conflicts between Europeans and Polynesians in Tahiti from 1767 onwards that resulted from the imperial expansion and rivalry of France and Britain in the Pacific.

During his time in London, Mai became a celebrity. There were paintings and plays about him. The newspapers reported on all of his adventures. However, Mai’s fame was not just confined to Britain. Due to a wider South Sea craze, he became an object of curiosity and entertainment for the whole of Europe. So Mai’s voyage and its cultural aftermath is by no means only a Pacific-British story. It also left its mark here in and around Berlin.

First, however, we might note that one would not necessarily expect Enlightenment art to focus on a Pacific Islander as a member of London’s high society. Though in fact, the Pacific was one, if not the central, geographical space that Enlightenment philosophy, literature and art dealt with during the late 18th century. In this period, European imperial expansion redefined itself as a scientific and philanthropic endeavour, and although it ultimately continued being about geopolitical influence, sea voyages to the Pacific were now also propagated in terms of Enlightenment ideals of knowledge and friendship. In the German-speaking world, the reception of the Pacific was closely associated with the naturalists Johann Reinhold Forster and Georg Forster, who set out for the Pacific with James Cook in 1773 – the very same voyage that would eventually bring Mai to London. The traces of this voyage, mediated by Mai’s fame and the Forsters’ work, have a lasting impact to this day.

When arguing these days about the provenances of the Humboldt Forum’s collection – like the impressive boats from the Pacific, for example – we should also keep in mind that the oldest Polynesian objects arrived there in the aftermath of Mai’s and the Forsters’ voyage. Today’s Humboldt Forum is located on the site of the former Berlin Palace, which housed the so-called Kunstkammer (cabinet of curiosities) of the Electors and Kings of Prussia-Brandenburg between the 17th and 19th centuries. It contained natural history objects, scientific instruments, works of art and artefacts from all over the world that were later to form the basis of Berlin’s museums. For Berlin’s aristocrats, the Kunstkammer was a valuable marker of social distinction: located right next to the palace’s two-storey grand ballroom, the royal family and their guests would visit it to marvel at the curiosities on display. An 1805 catalogue of the Kunstkammer lists “a beautifully woven tapestry from the audience chamber of Queen Oberea [Purea]” on which “[James] Cook and [Johann Reinhold] Forster sat.” (3) This tapa mat is still in the possession of the Ethnologisches Museum Berlin. Its presence in the palace’s Kunstkammer from as early as 1805, along with at least four other Tahitian treasures, testifies to the long fascination with the Pacific in the German-speaking world, but also to the long history of extracting knowledge and material culture from this region.

The central place the Pacific occupied in learned conversations between nobles and scholars during the Enlightenment can also be surmised from two other examples from our region: In 1794, King Frederick William II had a Lustschloss built on Peacock Island for himself and his mistress Wilhelmine Encke. Tahiti, “discovered” only 20 years earlier, served as inspiration for the building’s “Otaheite-Kabinett.” And as early as 1775, Prince Franz of Anhalt-Dessau had displayed a number of cultural objects from the Pacific in his castle in Wörlitz. He had received them from the Forsters immediately after their voyage, and the Forsters regularly used such gifts to curry noble favour and support for further endeavours.

My own work on the Pacific – especially my research with Lars Eckstein on ancestral navigational knowledge and practices in the Society Islands based on a map of the region made by Tupaia, a contemporary and compatriot of Mai’s – benefits directly from this heritage. (4) Important repositories of knowledge about the Pacific, such as the papers of Johann Reinhold Forster, are located here in Berlin. While I can visit these archives without much effort, people from Tahiti, Samoa or Vanuatu are denied direct access to them. So the question of how we address Germany’s entanglements in the Pacific comes up in my own work just as much as it does when looking at Daniel Boyd’s picture of Mai.

Daniel Boyd, Untitled (RMUFWM), 2022

courtesy: the artist and Roslyn Oxley9 Gallery, Sydney, photo: David Suyasa

Joseph Banks

Daniel Boyd, Sir No Beard, 2009

courtesy: the artist and Roslyn Oxley9 Gallery, Sydney, photo: Jessica Maurer

There is an obvious connection between the Mai painting and Daniel Boyd’s portrait of Joseph Banks as Sir No Beard. The British naturalist Joseph Banks first met Mai in Tahiti in 1769, and he acted as Mai’s host during the latter’s stay in London. In fact, in Joshua Reynolds’ portrait, Mai is in all likelihood wearing an item of clothing that Banks himself had brought back from Tahiti: a tapa cloth that belonged to the learned navigator Tupaia, who had intended to travel to Europe with Cook and Banks a few years before Mai, but had died en route.

Like Boyd’s painting of Mai, his depiction of Banks is based on a contemporary portrait. When Thomas Phillips painted him in 1810, he showed Banks at the height of his powers as the president of the Royal Society, to which he had been elected in 1778 and presided over for more than 40 years. Banks advised King George III on the layout of the Royal Botanic Gardens at Kew. In this capacity, he sent explorers and botanists to many parts of the world, making Kew Gardens arguably the most important botanic garden in the world. He supported several famous expeditions, including that of George Vancouver to the north-eastern Pacific and the voyages of William Bligh, who transplanted breadfruit trees from the South Pacific to the Caribbean islands where they were intended to provide cheap food for enslaved people. Banks lobbied for the British settlement of New South Wales and the colonisation of Australia, as well as for the establishment of Botany Bay (Sydney) as a convict settlement and basically advised the British government on all Australian affairs.

Boyd shows this Banks and his power, but he also shows him as a pirate who violently appropriates the property of others. But for today, I’d like to focus on the decapitated head floating next to Banks in a glass container. I know from the exhibition texts that Boyd is referring to Pemulwuy, a resistance fighter executed by British colonial authorities in 1802, whose head was cut off, conserved in alcohol and sent to Banks in London. But when the painting is shown in Germany, it also inevitably recalls an earlier trade in the looted bodies of Australian First Nations people that involved Banks. And this trade was with Göttingen.

In his role as a patron of natural history and an expert on Australia, Banks received a letter in 1787 from Johann Friedrich Blumenbach, a professor of medicine in Göttingen. At the time, Blumenbach was working on a taxonomy of humans based on comparing the traits of human skulls. Blumenbach thus wrote to Banks to ask for his help in acquiring such skulls from Australia and Tahiti. Banks himself was certainly familiar with this interest, having taken a head from Aoteara New Zealand back to London as a so-called “curiosity” during his circumnavigation of the world with Cook.

To my knowledge, however, Blumenbach was the first scientist to ask Banks for skulls for research purposes. After all, it was not until the 19th century that there emerged a larger interest in the racialising study of human remains; research that would draw on Blumenbach’s comparative studies of 245 skulls and skull fragments that he produced until his death in 1840. It was Blumenbach’s work in comparative anatomy that legitimised research on human remains as a scientific method and created the logistical infrastructure for systematic body snatching. As a result of his work, the bodies of Indigenous people became sought-after research objects. It was in this context that Pemulwuy’s head could be sent to London in 1802 simply as a matter of course.

Banks immediately undertook a search on Blumenbach’s behalf among the anatomical collections and private cabinets throughout Great Britain. But it was not until November 1793, almost three years later, that a human head from Australia was delivered to Göttingen by diplomatic post from London. It was – according to Banks – the head of “a male native of New Holland who died in our settlement of Sydney Cove.” A few months later Blumenbach also received the requested head of a “Tahitian woman” from Banks (5).

Who was the man from Botany Bay? In addition to his place of death (“in our settlement”), Blumenbach’s skull drawings indicate that he was a young man between 16 and 20 years old. Based on this data, Australian historians suspect that it could have been Baludarri, whose story is similar to Pemulwuy’s. Baludarri was a Burramatagal man from the Parramatta River near the penal settlement of Port Jackson who successfully traded fish with the British officers. In June 1791, this trade came to an abrupt halt when some convicts wantonly destroyed Baludarri’s canoe. His rage, as the diaries of the time describe it, “was unimaginable, and he threatened to take revenge in his own way on all the whites.” In the coming months, Baludarri injured a convict with his spear and organised a group of armed men who advanced to the outskirts of Port Jackson.

In December 1791, Baludarri fell seriously ill and died shortly afterwards on the way to hospital in the presence of staff surgeon White. According to European sources, he was not cremated, as was customary among the Eora, but buried on the grounds of the governor’s residence. So was it Baludarri’s head that Blumenbach received from Banks in 1793 and which is still in the Göttingen University collections today. Even if it is difficult to gather this information from colonial sources, this historical research constitutes a crucial step towards rehumanising the looted dead. Such provenance work is currently being undertaken as part of a Göttingen research project to identify the remains of some 1,300 individuals from colonial contexts in Africa, Oceania, Asia and the Americas in the university collections. Another, no less important way of engaging with this history came in the form of student protests in the summer of 2020, which opposed the uncritical commemoration of Blumenbach on the university’s campus and, in a symbolic act, laid a bust of Blumenbach flat on the ground.

Robert Louis Stevenson

Finally, I would like to return to Daniel Boyd’s version of the plate from the estate of Robert Louis Stevenson. Stevenson is a household name to most of us as a writer. Though I think only a few people are aware that, after arriving in Samoa, he soon took an interest in local politics and vehemently campaigned for the cause of the king claimant Mata’afa Iosefu against the colonial powers of the USA, Britain and Germany, who were vying for control over the island. In this context, Stevenson published a biting critique entitled A Footnote to History: Eight Years of Trouble in Samoa (1892). Following the text’s publication, Germany openly threatened to arrest and deport him from Samoa. The publication of any German translation of A Footnote to History was banned throughout the German Empire, and even the English edition was to be confiscated as an “anti-German pamphlet” and the respective owner fined.

Of course, Stevenson’s view of Samoa was also influenced by colonialism. Nevertheless, he was still a writer who agitated against the colonial powers. This is what Albert Wendt, the best-known post-colonial Samoan writer to date, has to say about Stevenson:

Later at university, while I was researching the Samoan Independence movement, I found A Footnote to History. For me, that has remained Stevenson’s most relevant work. It showed his astute and perceptive and enthusiastic support for our struggle against foreign powers and colonialism. (6)

Even some of Wendt’s own literary work is partly a “tribute to Stevenson” and an attempt to “reclaim” Stevenson for Samoa. To me, Boyd’s plate does something similar: it reclaims Stevenson, as well as Banks and Mai, for the Pacific. The plate from Samoa and its unexpectedly English floral motif invite us to recognise and trace Britain and Germany’s historical colonial entanglements in the Pacific and Australia. As a literary scholar, I find similar traces in the vibrant contemporary literature of the Pacific and Australia, which is populated by German colonial figures. Be it in the work of Albert Wendt and Sia Figiel from Samoa, of Selina Tusitala Marsh (with cultural roots in Samoa, Tuvalu and Aotearoa New Zealand), of Teresia Teaiwa from Kiribati – or in the recent award-winning novel The Yield by Wiradjuri writer Tara June Winch from Australia.

For me, their stories – much like the invitation to relationality in Daniel Boyd’s paintings – offer us important lessons about what it means to be entangled with the Pacific.

Anja Schwarz is Professor of Cultural Studies at the University of Potsdam. Her research focuses on cultures of colonial memory, Pacific navigation practices and Australian settler colonialism. As part of a German-Australian team, she is currently researching the collections of Prussian naturalists kept in Berlin institutions. These naturalists were active in the Australian colonies in the mid-nineteenth century.

Endnotes

1 See for example “Acknowledgement of Country.” Common Ground.

https://www.commonground.org.au/article/acknowledgement-of-country

2 First Nations (in Australia) is a collective term used for people with familial heritage from the first human inhabitants of Australia: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander nations. They are composed of many different Indigenous communities, each with their distinct languages, cultures and customs.

3 Henry, Jean. Allgemeines Verzeichnis des Königlichen Kunst-, Naturhistorischen und Antiken-Museums, Berlin 1805. GStA PK, I. HA Rep. 76 Kultusministerium, Ve, Sekt. 1, Abt. XV, Nr. 31, Bd. 1, p. 6–15.

4 Lars Eckstein & Anja Schwarz. “The Making of Tupaia’s Map: A Story of the Extent and Mastery of Polynesian Navigation, Competing Systems of Wayfinding on James Cook’s Endeavour, and the Invention of an Ingenious Cartographic System,” The Journal of Pacific History, vol. 54, no. 1 (2019), p. 1–95. https://doi.org/10.1080/00223344.2018.1512369

5 Turnbull, Paul. “Enlightenment Anthropology and the Ancestral Remains of Australian Aboriginal People,” in Voyages and Beaches. Pacific Encounters, 1769–1840, published by Alex Calder, Jonathan Lamb and Bridget Orr. Hawaii: University of Hawaii Press 1999, p. 202-225. https://doi.org/10.1515/9780824865511-013

6 Wendt, Albert. “Tusitala. The Legend, the Writer & and the Literature of the Pacific,” Preface of Robert Louis Stevenson. His Best Pacific Writings. Brisbane: The University of Queensland Press 2004, S. 9–11, here p. 10 (Translation: Anja Schwarz).