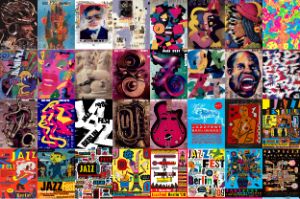

Design: Josefine Erbach, Daria Gumenyuk and Xaver Kamphues

Posterst © Berliner Festspiele / Jazzfest Berlin

Teaching Jazzfest Berlin

In the summer semester of 2024, two seminars were held at the University of Hildesheim and the Berlin University of the Arts on the occasion of the 60th anniversary of Jazzfest Berlin. The starting point for this was the festival management's decision to digitize the Jazzfest archive and make it available for research purposes. Being able to use these sources pragmatically and without much red tape in the seminars was a great gift for university teaching. These selected contributions provide insight into the results and findings of the seminars.

The content of this website was developed by students of the Berlin University of the Arts under the direction of Prof. Dr. Matthias Pasdzierny and students of the University of Hildesheim under the direction of Dr. Bettina Bohle in the summer semester 2024 as part of the seminars “60 Years of Jazzfest Berlin – Festival Studies and/as Musicology” (UdK, Berlin) and “60 Years of Jazzfest Berlin: Festivals as Crystallisation Points of Musical and Social Life” (University of Hildesheim).

On a Tuesday afternoon in the buildings of the University of the Arts Berlin an atmosphere prevailed of equal curiosity and scepticism. “Who here has already been to Jazzfest?” – Silence. “And who is into jazz?” – Roughly half the students raise their hands hesitantly, while the rest look around the room in faint embarrassment.

“Our background is in classical,” one voice says. This is how the seminar “60 Years of Jazzfest Berlin: Festival Studies and/as Musical Scholarship” by Prof. Dr. Matthias Pasdzierny, which has set itself the ambitious aim of integrating Jazzfest Berlin into academic discourse, begins.

Jazzfest Berlin was also studied at the University of Hildesheim in the seminar “60 Years of Jazzfest Berlin: Festivals as Focal Points for Musical and Social Life,” held on two weekends under the guidance of Dr. Bettina Bohle. For many of the students, this is their first encounter with the festival and with jazz music. One voice comments: “I have no emotional or professional connection to jazz and had no knowledge of Jazzfest.“

So where does such an exploration start? Where the story begins, of course: 1964, Joachim-Ernst Berendt, the Cold War. The participants in the seminar immerse themselves in old programmes, sifting through them, interpreting and analysing the material. They are intrigued, amazed and outraged about programming decisions and the use of certain terms that are now justifiably seen as problematic. Why does jazz always have to renegotiate its role, its identity and its legitimacy?

The first steps into this new material are hesitant but the energy of the invited guests soon spreads to all the anecdotes from the past create an unexpected familiarity with Jazzfest Berlin.

Nadin Deventer, Jazzfest’s Artistic Director, is present from the start. How is someone appointed to such a position? What experience is required to be able to select the right artists and make a mark? Discussions ensue about power, gender roles and sexism. Equal interest is generated by the question of what a music festival should and must achieve in terms of inclusion and diversity. An in-depth view behind the scenes unfolds.

Against this background, student research projects are launched: podcasts, posters, meta-programmes, interviews and video clips on topics such as racism, jazz and the division of Germany, gender roles, Jazzfest Berlin during the pandemic, and more.

These projects reflect not only the festival’s historical and cultural relevance, but also the sociopolitical dimensions of jazz.

The realisation that even large, state-subsidised cultural institutions such as the Berliner Festspiele and Jazzfest Berlin have to prove themselves in a competitive environment with small, often changing teams and that circumstances in the cultural sector as a whole remain difficult is a sobering one. At the same time, a deep admiration grows for the endurance and the passion underlying such events.

For us students, the experience of integrating Jazzfest Berlin into academic discourse was both enriching and inspiring. A veritable kaleidoscope of discoveries and insights is revealed in the broad range of quotations that are spread through the entire magazine. There is one thing left to say: look out, Jazzfest Berlin 2024 – we’re coming!

Ann-Sophie Werdich & Milena Brendel

This film was produced this summer by Jazzfest Berlin together with students from the Berlin University of the Arts and the University of Hildesheim. In this film, the participants give a first look at how they dealt with their research subject, the history of the festival.

Video “Introducing: Jazzfest Research Lab“ – Voices and impressions of the students and professors of the two seminars.

1

Seminarsasbridges:researchandartisticpracticeindialogue

A Conversation between Bettina Bohle and Matthias Pasdzierny

Bettina Bohle and Matthias Pasdzierny

Image editing: Lena Ganssmann

Bettina Bohle, director of the Jazzinstitut Darmstadt and lecturer at the University of Hildesheim, and Matthias Pasdzierny, professor at the Berlin University of the Arts [UdK], both held seminars on Jazzfest Berlin at their universities in the summer semester of 2024 to mark the 60th anniversary (entitled ‘60 Years of Jazzfest Berlin, Festivals as a Crystallisation Point of Musical and Social Life’ and ‘60 Years of Jazzfest Berlin - Festival Studies and/or as Musicology’ respectively). Here they talk about the different perspectives and shared insights that have emerged from their courses, both for the Jazzfest Berlin and for jazz historiography in German-speaking countries in general.

2

Interview

Julie Hofmeister talks to Julia Neupert

In the context of the course on Jazzfest Berlin, Julie Hofmeister, a student at the University of Hildesheim, conducted an interview with Julia Neupert, a jazz editor at SWR. In this conversation, Julie Hofmeister asks targeted questions about the development of jazz and the significance of Jazzfest Berlin. Julia Neupert shares her own experiences as a long-time journalist and festival attendee. The discussion highlights current trends, changes in the audience, and the festival’s openness to new musical and transdisciplinary approaches.

Interview Julia Neupert – Julie Hofmeister

3

Statistics

N-Word Graphic

Participants: Josefine Erbach, Daria Gumenyuk and Xaver Kamphues

The significance of the “encounter between black and white” is already mentioned in the foreword to the first festival programme booklet in 1964 under the direction of Joachim-Ernst Berendt. Over the years, the way in which this “encounter” is spoken about and dealt with has undergone a transformation. As part of the seminar at the UdK Berlin, a group of students investigated this very change using found objects from the Jazzfest Berlin programmes from the last 60 years. One result is this graphic.

The graphic shows how often the “N-word” has been used in the programme booklets since the beginning of the Jazzfest Berlin. Each tile represents a year. The diagram reads from top left to bottom right (top left tile: 1964, right adjacent: 1965, etc.).

The use of racist terminology in historical source texts is controversial; accuracy and transparency in academic citation are at odds with the injuries caused by the repetition of such terminology.

For more details on the related discourse in German-speaking countries, it references a recent article by Sina Delfs and Kaveh Yazdani, titled Critical Remarks on the Dominant 'N-Word' Discourse, in: Merkur, dated 12 April 2024.

www.merkur-zeitschrift.de/2024/04/12/kritische-anmerkungen-zum-herrschenden-n-wort-diskurs/

4

ReadySETJazz-Podcast

Gender, Race & Class

Ready SET Jazz-Podcast

Podcast Intro

A journey of discovery by three classical music nerds around the theme of jazz, explored through the lenses of gender, class, and race.

In a total of three episodes, we, Tiara Rhilam, Emilia Wünsch & Selda Tischler, talk about current situations, give you a historical overview, and have one or two interview snippets ready for you.

This project was created as part of our studies at the University of the Arts in a musicology seminar on Festival Studies and Jazz.

Tune in when it’s time to say: Ready, SET, Jazz

Ready SET Jazz 1

Gender: Women and Gender in Jazz

Jazz is a genre traditionally dominated by men, but women have also played a significant role from the very beginning. To learn how female artists stood up against prejudice and discrimination, be sure to tune in.

Podcast episode 1: GENDER

Ready SET Jazz 2

Race: Jazz and its History

Although jazz is celebrated worldwide as a symbol of freedom and artistic innovation, its development has been closely tied to racism and segregation from the very beginning. How does the Jazzfest Berlin deal with such a history? Be sure to tune in to learn more

Podcast episode 2: RACE

Ready SET Jazz 3

Class: Music and Privileges

What can be done to make live music accessible to a diverse audience? How can barriers be removed, and what is the Jazzfest Berlin doing about it? Tune in to learn more.

Podcast episode 3: CLASS

All sources were last accessed on 19.8.2024.